JULY

At the British Speedway Final on July 30, the new Weslake speedway engine swept its riders to first, second, fourth and fifth places. Peter Collins was second on the night, but went on to win Weslake’s first Speedway World Championship the following year

Words HUGO WILSON

In the mid-1970s, as the established British motorcycle industry lurched from one crisis to the next, there were still flickers of hope in UK based manufacturing and development. The Weslake speedway engine was one of them.

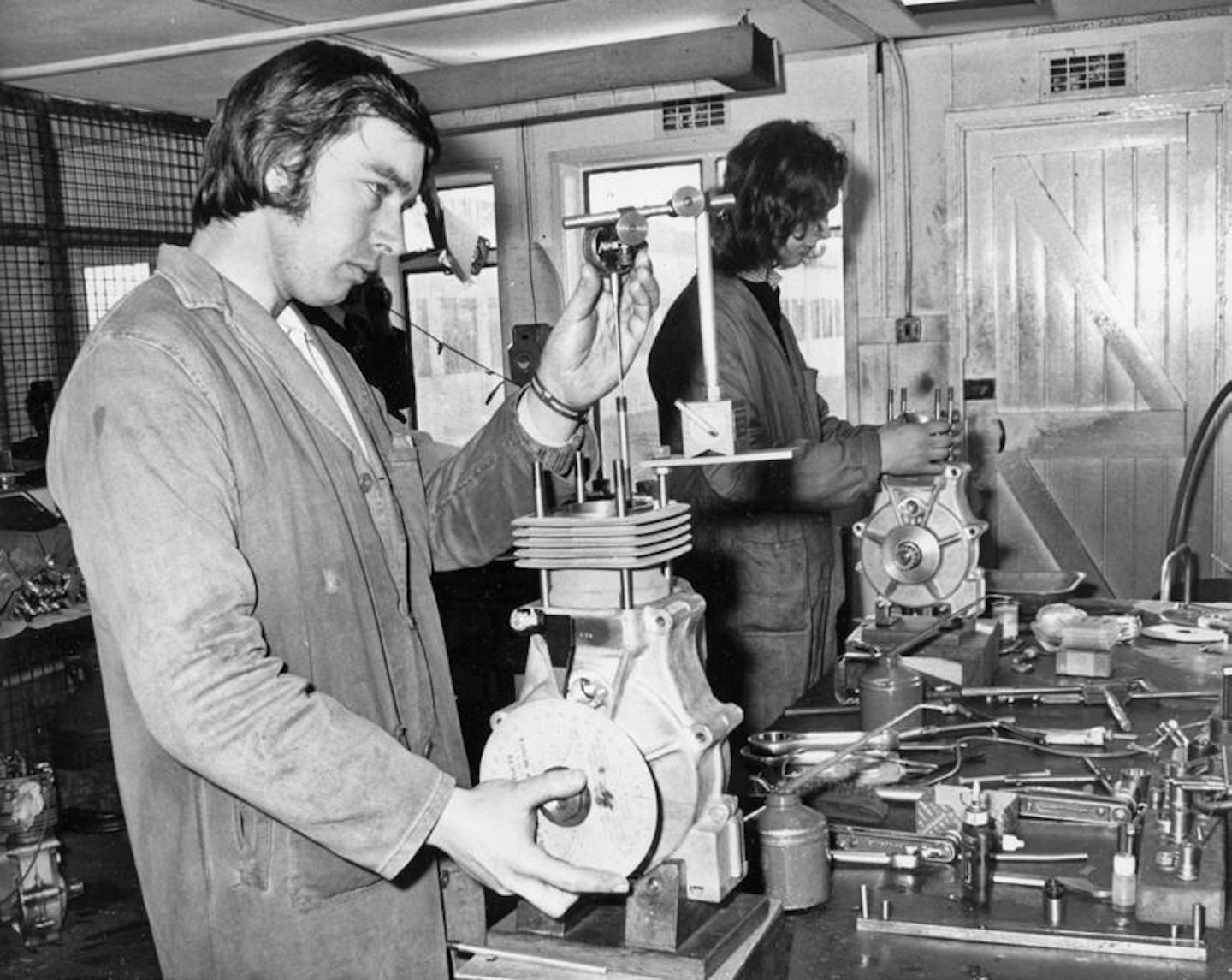

Weslake were a well established research and development engineers with a particular specialism in gas flow and four-valve cylinder heads. Company founder Harry Weslake had biking history going back years. During World War I, while still in his teens, he’d taken out carburettor patents. In the 1920s he prepared Sunbeam motorcycles for racing at Brooklands and developed a gas flow meter to test cylinder head efficiency. He went on to work with Bentley, Jaguar, Vanwall and other British motor industry giants. In the 1960s, among other projects, he developed the V12 engine for Dan Gurney’s Eagle Formula One car and made four-valve conversions for Triumph parallel twins.

The speedway engine wasn’t a commission. It was a response to the idea that the firm could build a four-valve engine that’d outperform the dominant two-valve Jawa, and which might be a commercial success.

Work had begun in 1974 and the prototype engine first ran at that October’s International Grass Track meeting at Lydden Hill in Kent, having been hastily assembled the day before. Ridden by Don Godden, who was involved in the bike’s development, the bike performed well in the final, but was thwarted by a lack of sparks. Peter Collins won on a Jawa, but he’d definitely noted the Weslake’s performance.

In December, with the engine now in a speedway frame, it was tested at Hackney Speedway track by Ipswich captain John Louis. He was impressed enough to order two units for the start of the speedway season in the following March.

The new engine used a flat-top piston and a narrow valve angle, with a pent-roof cylinder head. The four valves were opened by pushrods and the rocker layout was apparently informed by the work that had been done on Weslake’s four-valve conversion for the Triumph twin. It would safely rev to 8500rpm, with peak power (of around 45bhp) at 6500rpm. The new engine was designed with the same engine mounting positions as a Jawa unit, so it could be fitted straight into an existing frame.

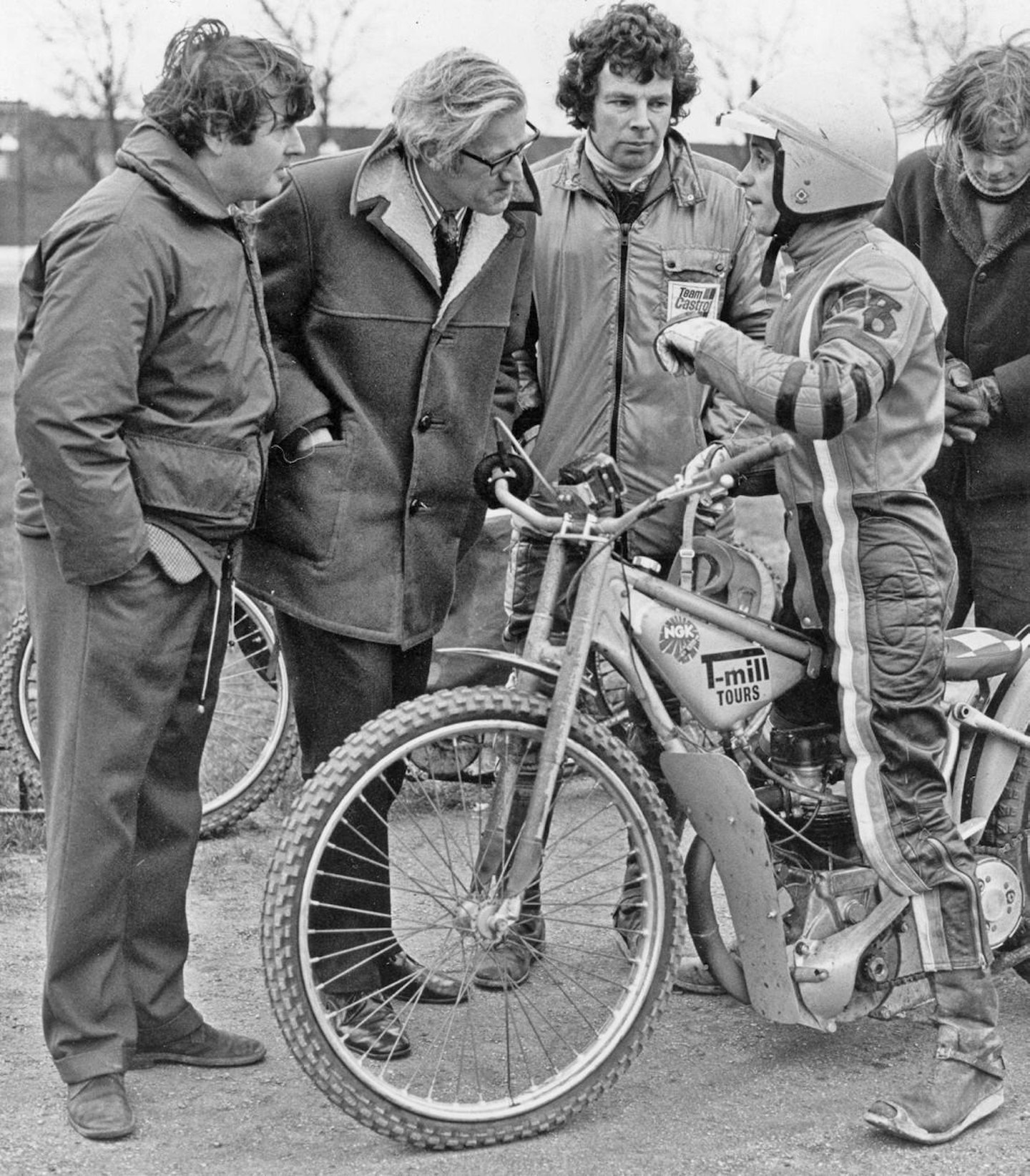

Despite having seen the prototype engine in action at Lydden Hill the previous year, Peter Collins – then one of the world’s top riders – wasn’t among the very early adopters.

“Dave Nourish was the northern distributor for Weslake. He took me down to the factory in spring 1975 and showed me what they were doing,” says Peter. “I hadn’t ridden one at that time. Then Dave brought an engine up for me to test at Belle Vue. I was impressed, but at the time I had the best two-valve Jawas prepared by Guy Hallet, so I wasn’t in a great rush to change. In truth, I was a bit slow.

“John Louis, Ray Wilson at Leicester and Martin Ashby at Swindon had been riding with them all season. And Phil Crump was riding a Jawa with a four-valve conversion. It was three months into the season before I raced the Weslake at the Golden Helmet competition. Phil Crump beat me, but I realised its potential as soon as I started using it. I knew that four valves were definitely the future. It was a big leap forward in terms of speed at the end of the straight and the pulling power out of corners was far superior.’

By the time of the British Final at Coventry in July, the Weslake was gaining real popularity among top riders. John Louis won on the night, ahead of Peter Collins, Malcolm Simmonds and Ray Wilson. Only Simmonds was riding a Jawa. By the end of the season, the majority of Britain’s top league riders were Weslake powered – and the success continued through the rest of the decade.

“I won the world championship in ’76 in Poland on a Weslake,” says Peter. “So I was the first world champion using a Weslake – and I stuck with them till nearly the end of my career. I was doing long-track and speedway, and the factory supplied me with about six or eight engines every year. The Weslake accelerated my career and helped me onto the very top rung of the ladder.’