Rick Rides

When the big names of the British bike industry amalgamated, it didn’t take long before cross-breeding took place. This month, our Rick tries out one of Norton’s more desirable desert sled hybrids

Words RICK PARKINGTON Photography GARY MARGERUM

It may seem a bit weird, the whole Norton/Matchless thing. We’re all used to hybrid concoctions like Tritons and Norvins – shed-built specials where enthusiast has mated one maker’s engine with another’s chassis – often the Norton Featherbed – but this is a factory bike. What’s more, it’s a Norton without its Featherbed; an Atlas engine stuck in a Matchless frame, of all things. It’s also an off-roader, built in the late sixties when the UK café racer boom was at its peak – and stranger still, a 750. Few people associated engines that big with knobbly tyres until over a decade later, when those crazy continentals started going for the big trailies that ultimately spawned today’s huge ‘adventure bike’ market.

Well, I have to admit riding the P11 off-road feels a bit of an adventure. It’s certainly got the low-down power to kick up a rooster tail when asked, but I feel a bit uneasy riding around this field. Admittedly, the ’bars are pulled back a bit further than I’d choose – and I’ve never claimed to understand handling and how to alter its characteristics, but while it feels stable enough I’d say there’s enough understeer to suggest that the front end is kicked out a bit too much for this type of riding. So I find myself hovering a supportive foot off the peg more than I’m used to. The motor is certainly gutsy enough to pull up a bank – although, again, the gearing really isn’t low enough for that type of work, at least if you want to use any finesse.

But the P11 was no more intended for some fool to ride round an English meadow than it was for the Scottish Six Days Trial. This is a desert racer, born to blast across a shimmering, sun-bleached surface to some distant point – commonly marked by a pile of burning tyres – and race back again. Desert racing is a kidney-bashing speed event where the most nadgery work will probably be getting the bike on and off the pick-up. These bikes needed to be geared for high speeds without losing bottom-end grunt, and to have good straight-line stability over rough ground. Looked at that way, the P11 scores well – and not only in the desert.

These qualities also make for a good scratcher’s bike; I’ve said before that I wish I ’d realised in my untamed youth how good desert racers like this are for hassling newer bikes on twisty roads, and I’m reminded of it once again. There’s something hugely confidence-inspiring about narrow tanks and wide ’bars that may help explain why those who learn to ride on dirt bikes are typically capable in other disciplines. Sitting up high is more relaxed than hunching down on a café racer – and relaxed and confident is a good place to be on a bike.

I’m really impressed with the P11. The Norton gearbox and clutch are strong and positive as usual – and one advantage with all the hybrids is that the closer spacing between engine and ’box allows use of AMC’s cast alloy chaincase, where other Nortons had to make do with their pre-war, leak-prone pressed tin case right up to the Commando. Unusually among the hybrids, the P11 uses AMC rather than the larger Norton brakes, but they worked well on the test bike – probably aided by the bike’s low weight.

Despite the big engine, it was also an easy starter – the P11 was also the first hybrid with coil ignition, rather than a magneto. That was unpopular among desert riders, but Lucas were keen to cease costly magneto production and had just created their 2MC capacitor that permitted battery-free running. I had no further criticism of the steering as I swung through Macadamed curves, suggesting that I’m right to think it’s set-up for faster work than grass. I was also surprised how smooth it felt, with nothing intrusive at the 50 70mph speeds I was doing – even though the Norton Atlas was famous for severe vibes.

Like other British parallel twins, the Norton started as a sweet 500. It was designed by Bert Hopwood in 1948 as a quick response to post-war demand for parallel twins. Hopwood saw it as a quick-fix design that should last until something better could be conceived – and later expressed his anger that management never investigated a more future-proof design. Instead, his ‘Dominator’ twin grew from 500 to a useful 600cc, then a 650 – until, with the 750 Atlas, vibration started to become a real problem. Rubber ‘Isolastic’ engine mounting on the 750 Commando successfully dodged the problem and justified a further increase to a blistering 829cc.

Let’s hope Hopwood drew some satisfaction from how well his ‘temporary’ design coped – especially considering the John Player racers. Like the Atlas, the P11 doesn’t benefit from Isolastic rubber mounting, but whether this bike’s had the crank balanced or it’s just a feature of the different chassis, the impression I got from the P11 was that it wasn’t a shaker.

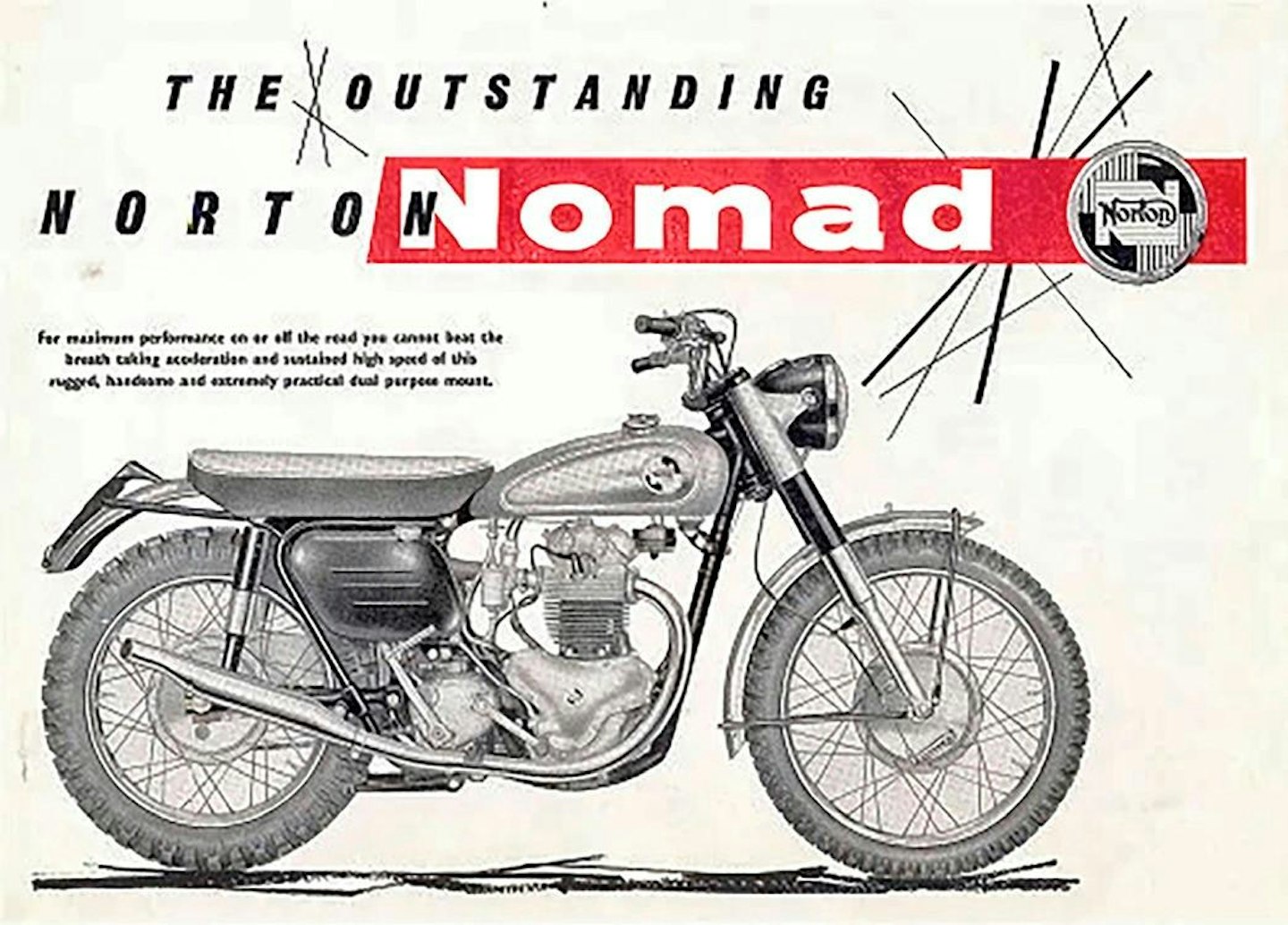

The background of the P11 lies in earlier Norton/ Matchless hybrids. After a decade as part of Associated Motor Cycles (the AJS/Matchless conglomerate), in 1962 Norton moved south from Birmingham to the Matchless works at Plumstead, London. For some years, all the three makes had in common was the gearbox; as Nortons retained their defining Featherbed frame, its widely-spaced horizontal top tubes dictated a stye of tank and saddle very different to AJS/Matchless models. But the TT-derived Featherbed was not at all suitable for off-road use, and with increasing demand for scrambler models from the States the only option had been to use the earlier single-downtube pre-Featherbed frame to create a more appropriate model – the 600cc twin-cylinder ‘Nomad’. But it was an obsolete frame, and with Norton’s move to Plumstead it made sense to employ an existing AMC chassis for future export scramblers – and that wasn’t simply an economic decision.

Matchless was a popular brand in the States; it had been one of the makes distributed by Indian after their own production ceased and was then taken on by the Berliner Corporation of New Jersey. Much of the good name Matchless enjoyed in the States came from their off-road big single, the 500cc competition model G80CS. In 1966 the G80CS became the G85CS, which had a bespoke frame that leaned heavily on the Rickman Metisse design. Better braced, it was of largely welded construction, in contrast to the old roadsterbased heavyweight, brazed-lug Matchless type on the G80CS which made it some 45lb lighter.

But while these singles were good sellers in the States, the twins fared less well due to increasing reliability problems as capacity grew to 646cc and was then squeezed for more power to provide sports CSR outputs. Cycle World brutally recalled the history of the 650 Matchless as ‘punctuated with the thud of exploding engines’, so we can’t be surprised that Joe Berliner, head of the import corporation, was taken seriously when he suggested the Matchless twin might be easier to sell if it was fitted with the tough Norton 750 motor – making it more reliable under the guise of enlarging capacity.

The factory acted and the result was the Matchless G15/AJS Model 33 hybrids. Although primarily aimed at the US market with open pipes and dirt tyres, they were also available for road use with lights and room for a pillion. UK models were marketed as CSR sports roadsters; but despite being equipped with fashionable aluminium mudguards, flat ’bars, rearsets and sweptback exhausts, the legendary status held by the Featherbed frame in café racing circles resulted in limited UK sales compared to Norton’s 650SS and 750 Atlas.

And anyway, there was much more than that to worry about. The AMC empire was foundering and in August 1966, the Official Receiver was called in to sort out the situation for AMC’s many unhappy creditors. The company was sold to Manganese Bronze Holdings who, having already pulled Villiers Engineering Co from the cliff’s edge, formed Norton Matchless Ltd as a division of a larger company, Norton Villiers Ltd, of which more would be heard in subsequent years.

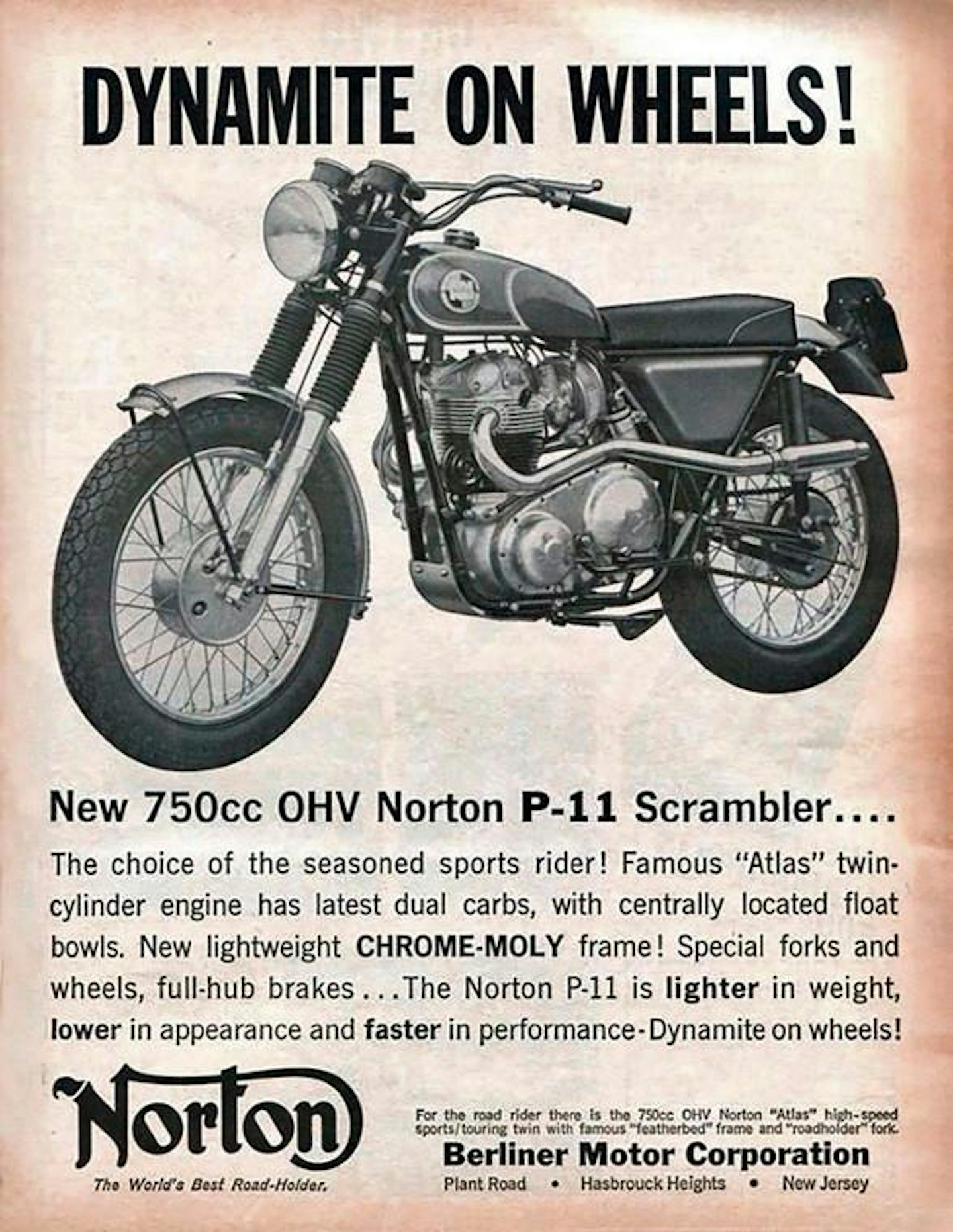

As if in anticipation of this, there were two Nortonbadged hybrids produced for 1967. The first was simply the G15 with Norton badges, unimaginatively named the N15. The second, though, was much more convincing. ‘Project 11’, so the story goes, was the work of Berliner’s Western Distributor, California dealer Bob Blair. The hybrids had always been on the heavy side and Blair decided to make a lighter, more competitive version by adapting the chassis of a wrecked G85CS in his workshop to take an Atlas motor.

After convincing Joe Berliner that it was a good idea, the bike was shipped across to the UK for factory evaluation. It became the Norton P11, having its show debut that autumn – sharing stand space with the new 750 Commando, illustrating the direction the company was headed. The P11 was in production for less than two years. For 1968, it became known as the P11A and later the ‘Ranger’, indicating a move to increase the P11’s appeal for everyday use by adding a dual seat along with more convenient low-level exhausts.

That makes sense to me; despite my off-road doubts the P11 is a stonking bike to ride on the road – and while I don’t regard motorcycles and sand as a good mix, I’d risk it to give a P11 a good blast across the desert. Dammit! Dreaming of powering through the scrub toward those burning tyres, I inadvertently got onto the slip road to a busy dual carriageway – not the place for an old off-roader... or so I thought.

I gunned the Norton up and it stormed into the melée like a pub brawler, subjecting the occupants of executive cars to its impressive war cry. I’d forgotten that while big Norton twins develop a lot of power low down, that doesn’t mean that they don’t have a lot higher up too. I came off at the next exit, having made my point; that riding position would soon get tiring at speed – but the P11 isn’t a contender for ‘classic adventure bike’, it’s made for high-adrenaline ride-outs and makes a great way to blow away the sticky cobwebs of modern living, which is what classic bikes are about in my view.

SPECIFICATION

1967 NORTON P11

ENGINE/TRANSMISSION

-

Type 360° four-stroke parallel twin

-

Dimensions 73 x 89mm

-

Capacity 745cc

-

Power 52.5bhp at 6400rpm

-

Compression ratio 7.5:1

-

Carburation Two Amal Concentric Mk1 30mm

-

Clutch Wet multiplate

-

Gearbox Four speed

CHASSIS

-

Frame Welded, tubular steel, twin-downtube cradle

-

Front suspension AMC Competition Teledraulic telescopic fork

-

Rear suspension Twinshock, swingarm

-

Brakes Front: 7in (178mm) single-leading-shoe drum. Rear: 7in (178mm) single-leading-shoe drum

-

Wheels Spoked

-

Tyres Front: 3.50 x 19. Rear: 400 x 18

DIMENSIONS

-

Wheelbase 57.6in (1463mm)

-

Weight 368lb (167kg)

-

Performance Top speed 110mph

-

This bike is available from Anthony Godin, £12,995 anthonygodin.co.uk

Norton’s off-road family

1958 The enduro-style Nomad is introduced using the old Norton Model 77 single-downtube frame. Equipped with a 21in front wheel, tuned twin-carb 600cc Dominator engine and lights, it is aimed at the US market.

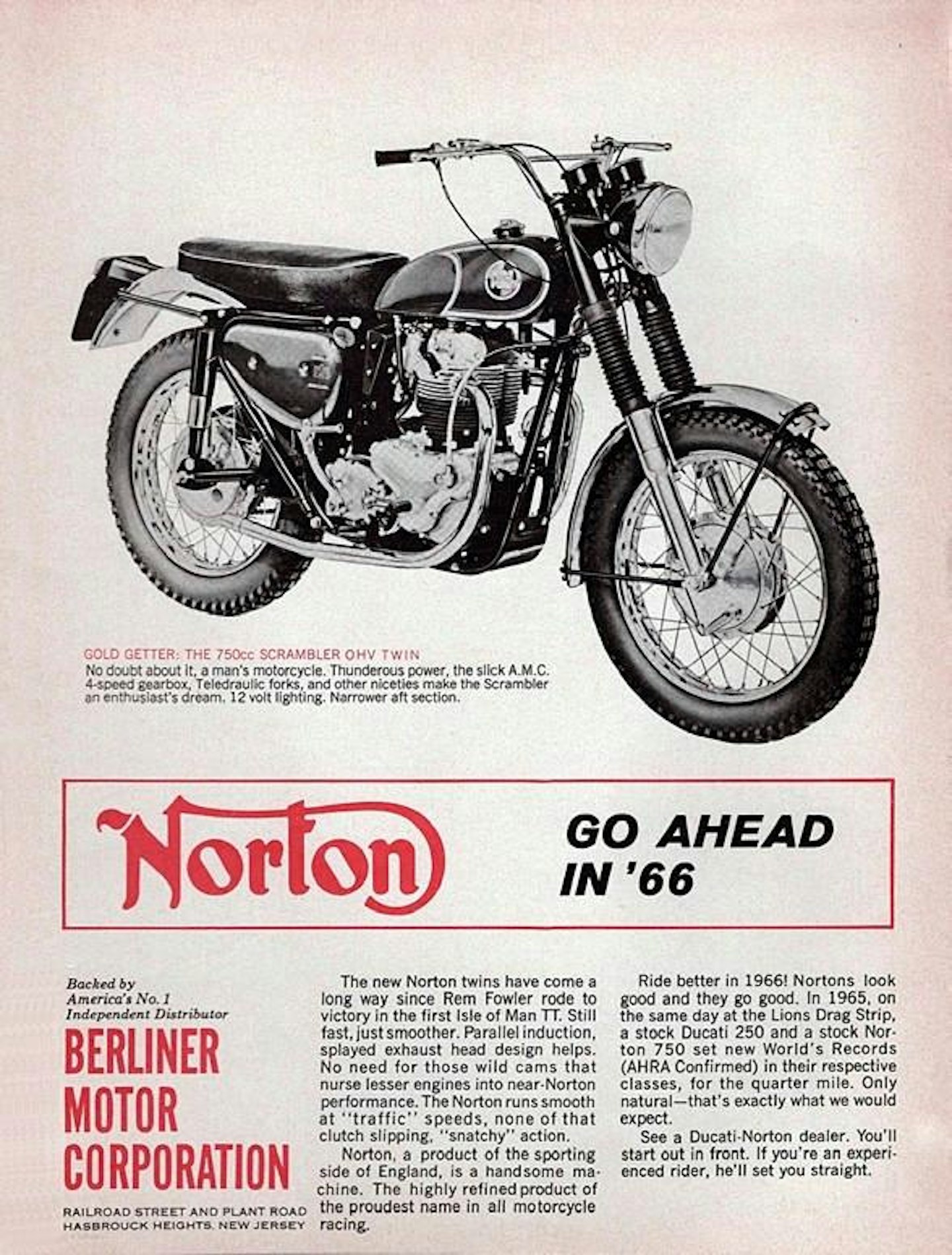

1962 Norton production moves to the AMC works at Plumstead, South London – and a new model, the 745cc Atlas, is introduced, initially only for export and UK Police use.

1963 The Atlas engine is fitted into a Matchless CSR-type frame to create the hybrid Atlas scrambler. As well as the engine and gearbox, it uses Norton wheels and Roadholder forks.

1965 With the Norton Atlas already available on the home market, its engine is fitted to a sports roadster hybrid – the Matchless G15 CSR (or AJS Model 33 CSR) offered for sale to UK buyers.

1966 The AMC company goes into receivership and is incorporated into Norton Villiers Ltd.

1967 A Norton version of the G15 – the N15 – is created along with the P11, another hybrid this time using the lightweight Matchless G85CS competition single frame and forks with Matchless wheels.

1968 The P11 is now the P11A, made more suitable for all-round use with low exhausts and a dual seat. It is then named ‘Ranger’, but is discontinued before the end of the year along with all other Norton/Matchless hybrids, leaving just the Featherbed Norton 650 Mercury and the new 750 Commando.