Rick Rides: EGLI-VINCENT

Norvins reignited interest in Vincent in the ’50s, before Egli did the same in the ’60s. As the owner of one of the former, Rick’s well placed to judge the latter...

Words RICK PARKINGTON Photography GARY MARGERUM

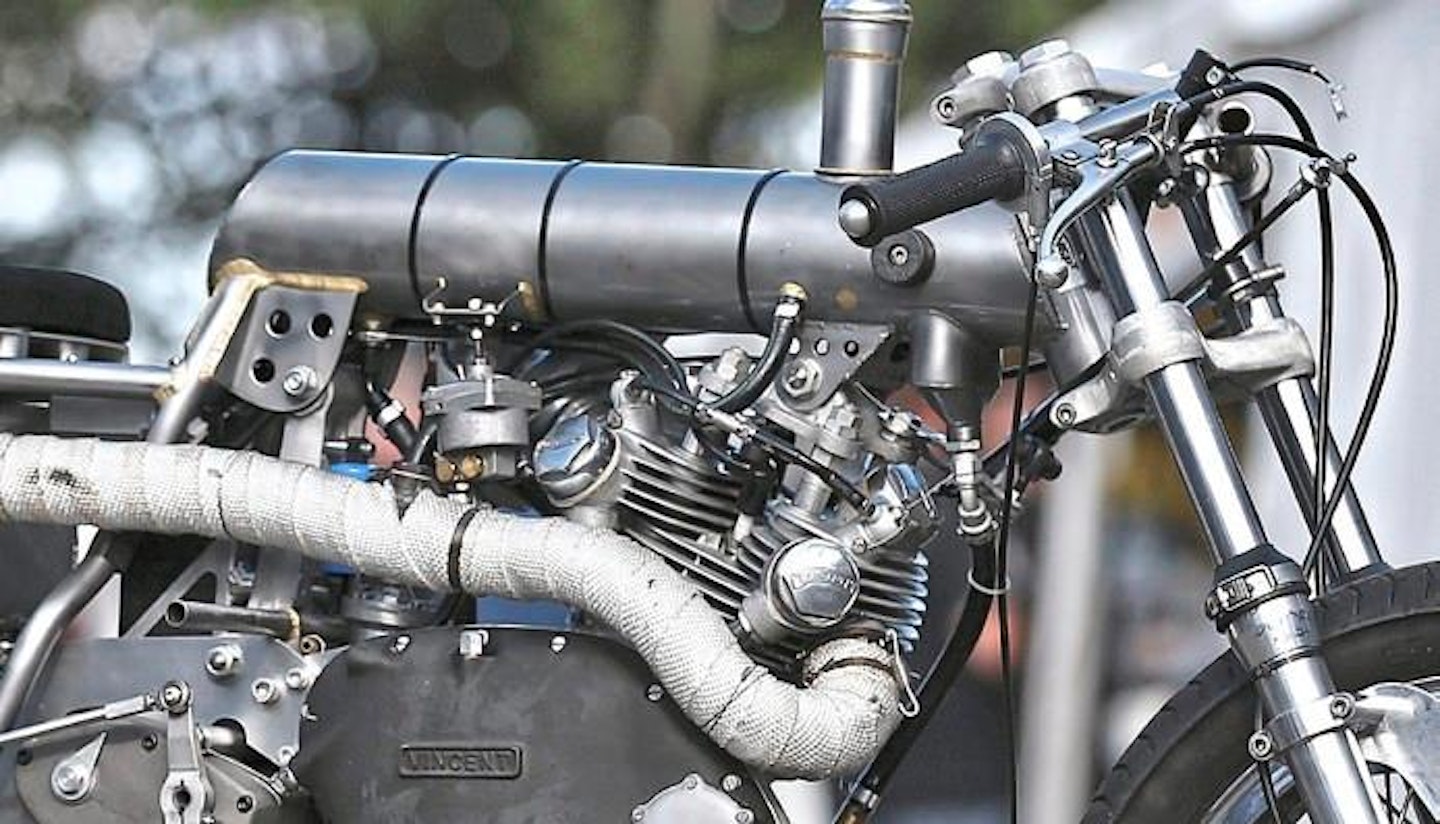

I should declare a ‘conflict of interest’ here. This Egli Vincent is a beautiful bike, hand built by an engineer to an exacting standard. It runs beautifully, sounds crisp, stops on a sixpence and the handling is absolutely superb. Widely considered the ultimate Vincent special, when done properly the Egli is one of those überclassics that some would describe as ‘incomparable’.

And that’s the problem. I can’t help doing just that – comparing the Egli to the Vincent special that I rode here today, my unassumingly shabby (if well-loved) Norvin. I deliberately chose it this time, because I’m genuinely curious to learn just how different the two bikes will be. My bike is not a café racer – it’s in standard Norton Dominator trim, but while the Egli has clip-ons and rearsets, the bars are positioned high, like straights. So it’s comfortable – less café racer, more ‘sports tourer’, which is essentially what Vincents were in the first place.

Like a Rickman, the Egli was really just a racebred replacement chassis, designed to offer upgraded roadholding characteristics – if owners wanted it to look like a racer, that was up to them; it doesn’t have to.

‘The Egli was just a race-bred replacement chassis which offered upgraded roadholding’

Unfortunately, the day started badly. Kicking the Egli over, the non-standard kickstarter snapped, the attached end springing back to deliver an accurate karate chop to my ‘old war wound’. The pedal looks like a modified Honda CB750 item, as skinny as Bambi’s foreleg, but it’s the only option; this is one of those ‘Vincent things’. ‘Unconventional’ describes most aspects of Vincent design, and their upended gearbox layout, with its kickstarter shaft at the front and gear pedal behind, means the Vincent kickstart can’t work with alternative footrests – the long Honda pedal swings out far enough to clear. Bump-starting big tall-geared Vtwins is hard work – but fortunately the Egli was an excellent starter, so the day wasn’t spoiled.

The first thing I noticed was the clutch – it’s feather light. Although Anthony Godin (who was selling the bike at the time of our test, although it’s now been sold) thought it was a Norton item, I’d guess it’s more likely the original Vincent. Vincents have a servo clutch that takes the power, the hand lever operating just a lightweight plate-type for pulling away. My Norvin came fitted with a Commando clutch and it was diabolical. There wasn’t enough lift in the Vincent mechanism and it dragged horribly in traffic. I’ve fitted a Suzuki GS1000 clutch using an adapter – it’s also light and works OK, but just OK because the Vincent’s higher primary-drive ratio loads it more heavily than the Suzuki. The Egli’s gearing is also better; the mismatch between Vincent and Norton sprockets means my Norvin seldom reaches top on pootling roads; the Egli’s Triumph conical hub has a bolt-on sprocket offering more choice.

But the most obvious difference between the two bikes is handling. Both handle well, but the Norvin feels much more committed to a line; that is, having chosen your path it prefers not to deviate. The Egli feels more modern – not just because of the contemporary suspension, it’s just more flickable than the Norvin and happier to accept adjustments mid-corner, which has to be an improvement over the Featherbed. It was always said of Manx Nortons that they’d hold a line perfectly – but once they let-go, you were off. The Egli feels more forgiving. The suspension complemented the rest perfectly; the forks are from a modern Triumph and their twin discs with four-pot calipers were also appreciated, because the Norvin’s single-leading-shoe Norton drum struggles with the weight a bit.

Of course the Egli frame is an improvement; Norton’s McCandless-designed Featherbed frame took chassis design out of the 1930s; it deserves its legendary status and its echoes can still be seen on modern sports bikes – but Vincent engines were never intended to fit in a cradle frame, making the Norvin a compromise.

Egli’s frame was not a compromise; it was designed around a Vincent engine, following similar principles.

Philip Vincent didn’t approve of people fitting his engines into (as he saw it) inferior frames. Having designed his own unconventional design with monoshock-style rear suspension way back in the late ’20s, it puzzled and exasperated him that, despite proving the worth of his concept, the industry settled for the bendy and unsupported swingarm over his triangulated suspension system. Worse still, people were fitting his engine into such frames – and the Norvin was probably the primary offender.

‘Fritz Egli’s racing success attracted orders for frames from other riders’

By the mid-1950s, while the clean lines of the big alloy motor still attracted admirers, the Vincent chassis looked dated; no wonder people sought to fit these engines into a famously successful racing frame. Probably the first recorded sighting of a Norvin was a 1955 photo taken by Geoff Duke in Australia of the ‘McCrae Special’ – sidecar racer Sandy McRae’s Black Lightning-engined Manx – and Vincent-power was cool again.

Fritz Egli did it differently. The Swiss racer had competed on his tuned Rapide for a couple of years before reflecting that the advantage Norton had gained from updated chassis design could be applied to his Vincent. Rather than build a Norvin, Egli created his own frame. Like a Vincent, the oil was stored in a large frame member under the tank that was strong enough to support the weight of the engine. By 1968 his racing success was attracting orders for frames from other riders and the Egli Vincent was born.

With Vincent engines in finite supply, gradually Egli evolved his design to cater for high-performance Japanese engines – the CB750, Z1... even the Honda CBX – but despite Eglis later efforts, the name is still inextricably connected with Vincent, and the Egli Vincent remained in production until the end. But how on Earth can an engine designed in the 1940s be considered worth not one but two regenerations to meet the challenges of a new era?

I think there are two answers. The first can be found by riding this glorious Egli – or even my own shabby Norvin. Vincent engines are special. They manage to combine the character and ‘olde worlde charm’ of a 1930s single with enough roadgoing capability to exist in the 21st century. You don’t need one of the Godet 1300 engines with their mighty dollops of extra horsepower to discover this; a standard Rapide will do. The Vincent has stamina; it has just the right balance of capacity, power and heavy metal innards to pull a high gear and can sit happily at 80-plus on a motorway, with the addition of a passenger or luggage not affecting it. It’s the most relaxed old British bike I’ve found for motorway riding. In short, Vincents are pretty impressive for a 78-year-old design.

The other answer is the Vincent legend. Legend is an over-used word nowadays, applied to anything that’s just a bit better than the rest. True legend has to have a spark of magic about it – like that iconic image of Rollie Free, flat out at Bonneville in his Speedos, or Phil Vincent’s almost OCD insistence on making his personal idea of a perfect motorcycle, irrespective of how much it cost, his blind faith in other motorcyclists knowing a good thing when they see it as his guide and to hell with the accountants. I’d want it to be like that if I made a bike – you’d probably be the same. But the real magic here is that this ‘nutty professor’ character with his absurdly complicated solutions to technical problems nobody else had ever noticed – solutions that created problems of their own – somehow actually got it right in creating something that, while it never sold enough to sustain his company, was a born classic that’s still great to ride all these decades later. I’d say that deserves a better – sorry Phil, let’s say ‘more modern’ – chassis and brakes, so it can still hold its own on today’s roads.

What about me – would I part-ex my Norvin for the Egli? No, I’m afraid not. The Egli is the better bike, but I live in the past and I find mixing modern and old too jarring. I dreamed of owning a Norvin at the age of 16, and having brought my dream alive I’m not after an upgrade. But admittedly, riding the Egli has reminded me I must look out for a twin-leading-shoe front brake for it...

BUILDING ONE TODAY

The passing of passionate Vincent specialist Patrick Godet in November 2018 created a hiatus in new Egli production. In 1970s England, Slater Brothers had frames made by Cheney under licence from Egli and in more recent years John Mossey Restorations bult replicas – but it was Patrick Godet in France who received Fritz Egli’s blessing to take over manufacture of the ‘Egli Vincent’ he created. Godet further developed the concept with new 1330cc engines of improved build quality and performance. Godet’s company survives him, but in the years since his loss, the classic world has gone through big changes.

“I don’t think anyone is making new frames at present,” says Steve at Vincent specialists Conway Motors. “But there are still plenty around. We can build Eglis for customers, but I think the last Godet Eglis were something like £46,000 with a two-year waiting list – and, now that Vincent prices have stopped spiralling, few customers want to wait two years when they can pick one up secondhand with virtually no miles on it for a lot less.

“If someone supplies the chassis, we can build a completely new engine from parts for around £26,000, depending on specification. Obviously, if you supply some of the parts yourself it will be less – but again, be careful. There’s ‘basket case’ engines and bits around that are basically just rejects from a rebuild –and you won’t save anything by supplying us with scrap crankcases, heads or cranks!

“The really crazy thing about it is that the obsession with ‘original’ bikes means that you could probably pick up a non-matching Rapide for about the same price as a new engine and just take the motor out of that, selling the chassis on as parts! I understand ‘matching numbers’ on bikes where specifications varied, but Vincent parts hardly changed at all. Numbering both halves of the frame was probably the worst thing Vincent ever did – without that, nobody would know or care!”

**

SPECIFICATION - 1950 EGLI-TYPE VINCENT RAPIDE**

ENGINE/TRANSMISSION

-

Type 50° air-cooled pushrod V-twin

-

Dimensions 84 x 90mm

-

Capacity 998cc

-

Power 45bhp at 5300rpm

-

Compression ratio 6.45:1

-

Carburation Two Amal 930 Concentric Mk1s

-

Clutch Dry Vincent servo

-

Gearbox Four speed

CHASSIS

-

Frame Oil-bearing, tubular steel with engine as stressed member

-

Front suspension Hinckley Triumph telescopic forks

-

Rear suspension Pivoted fork with twin shock absorbers

-

Brakes Front: Twin 10in (254mm) disc with opposed four-piston calliper.Rear: Triumph Conical Hub 7in (177mm) sls drum

-

Wheels Spoked with flanged alloy rims

-

Tyres Front: 110/80/18. Rear: 130/80/18

DIMENSIONS

-

Wheelbase 55.75in (1416 mm)

-

Weight 429 lbs/195 kg

PERFORMANCE

-

Top speed 115mph