THE WORKSHOP: KNOWLEDGE

The conventional roller chain has largely been superseded by sealed-ring designs on modern bikes, but should we be fitting them to classics too?

Illustration REGINA INTERNATIONAL LTD Photo JAQUES PORTAL

Alan Seeley

‘I won’t skimp on chains, because the cheap stuff soon stretches and sags – particularly if you like to hammer on and off the throttle and you’re a bit shy with the chain lube.’

What are the options?

STANDARD ROLLER CHAIN

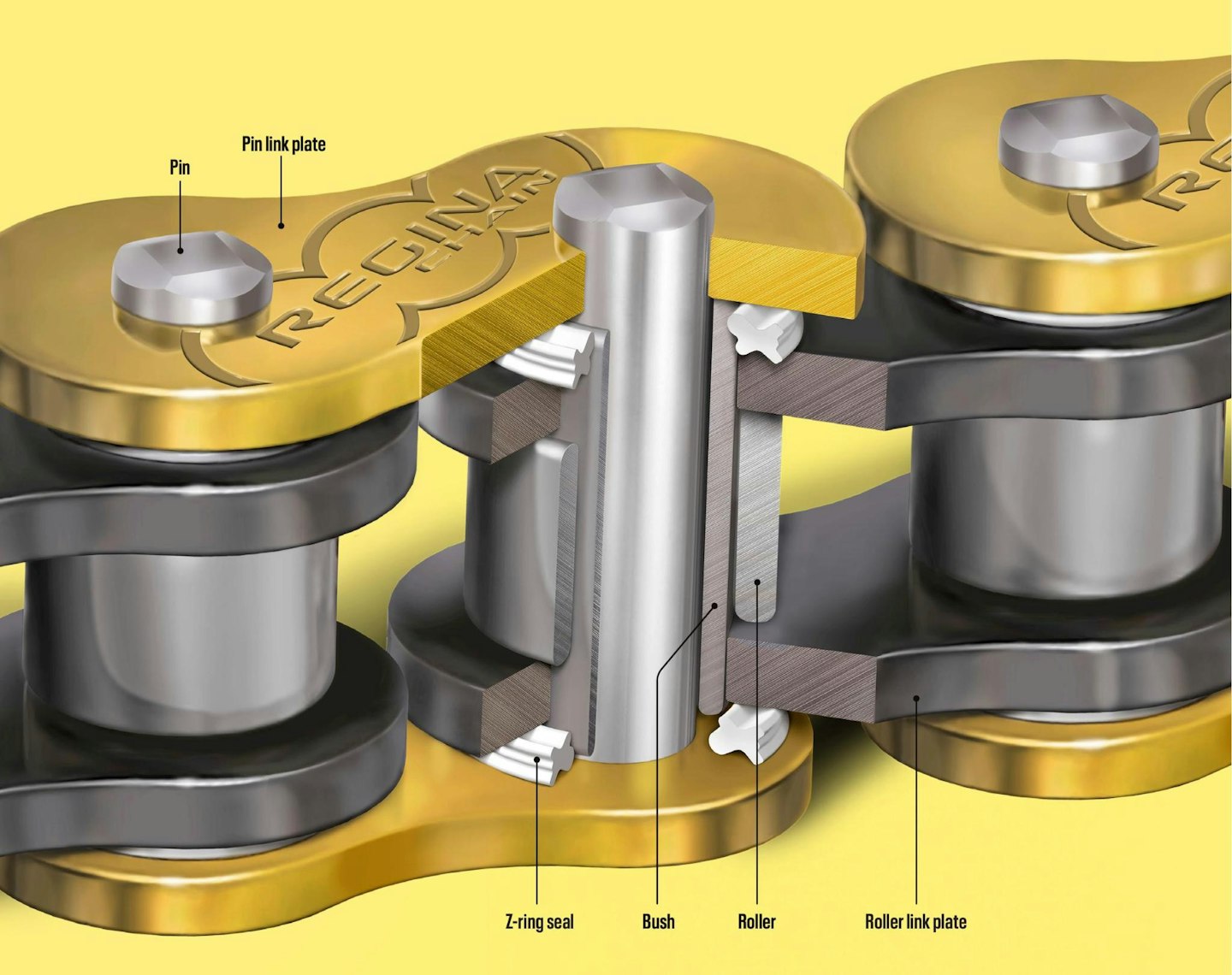

The standard roller chain, consisting of basic links with pins and rollers, was original fitment to older classics. A roller link is composed of two sideplates with hollow bushes pressed into them and a roller that’s free to rotate on each of those bushes. A pin link has pins pressed into sideplates; these connect the hollow links with the pins passing through the bushes in the roller links. The pins rotate in the bushes and the rollers spin on the bushes.

There are also solid impregnated roller chains in which the roller and bush are combined into a single fixed piece and the pin links rotate within them; the chain lube or oil lubricates the gap between pin and bush. Us older riders remember heating a tin of lube on the stove to immerse chains in, while mother/the other half was out. We also remember when chains seemed to need adjustment every week.

+ Pros Cheap to manufacture and hence cheaper to buy. Lighter and less bulky than O-, X- and Z-ring types.

- Cons Need more frequent oiling than sealed types. Dirt and grit can wheedle its way into links to form a grinding paste with oil and lube.

O-RING, X-RING AND Z-RING CHAIN

The O-ring chain was invented in the 1970s and became common fitment to motorcycles the following decade. The basic construction of sealing ring chain is like that of a standard roller chain, but with the addition of seals between the roller links and the sideplates of the pin links. These seals serve the dual purposes of containing the lubricant that’s injected between the pins and bushes when the chain is manufactured, and keeping dirt and moisture out when in service.

X-section rings were an evolution of the O-ring, intended to reduce drag and improve sealing. Z-ring is a further evolution by Regina. The O-ring has a single, wide sealing face on each side once squeezed between the roller and pin links. Later versions are designed to provide a better seal, to keep grease in and cack out, while also reducing friction, which can be significant.

+ Pros Longer life and less frequent lubrication and adjustment required, if quality material and construction is used.

- Cons Heavier, wider and more expensive than standard roller link chains. Needs a special tool for fitting the rivetted link, although some can use a spring link.

What do the numbers mean?

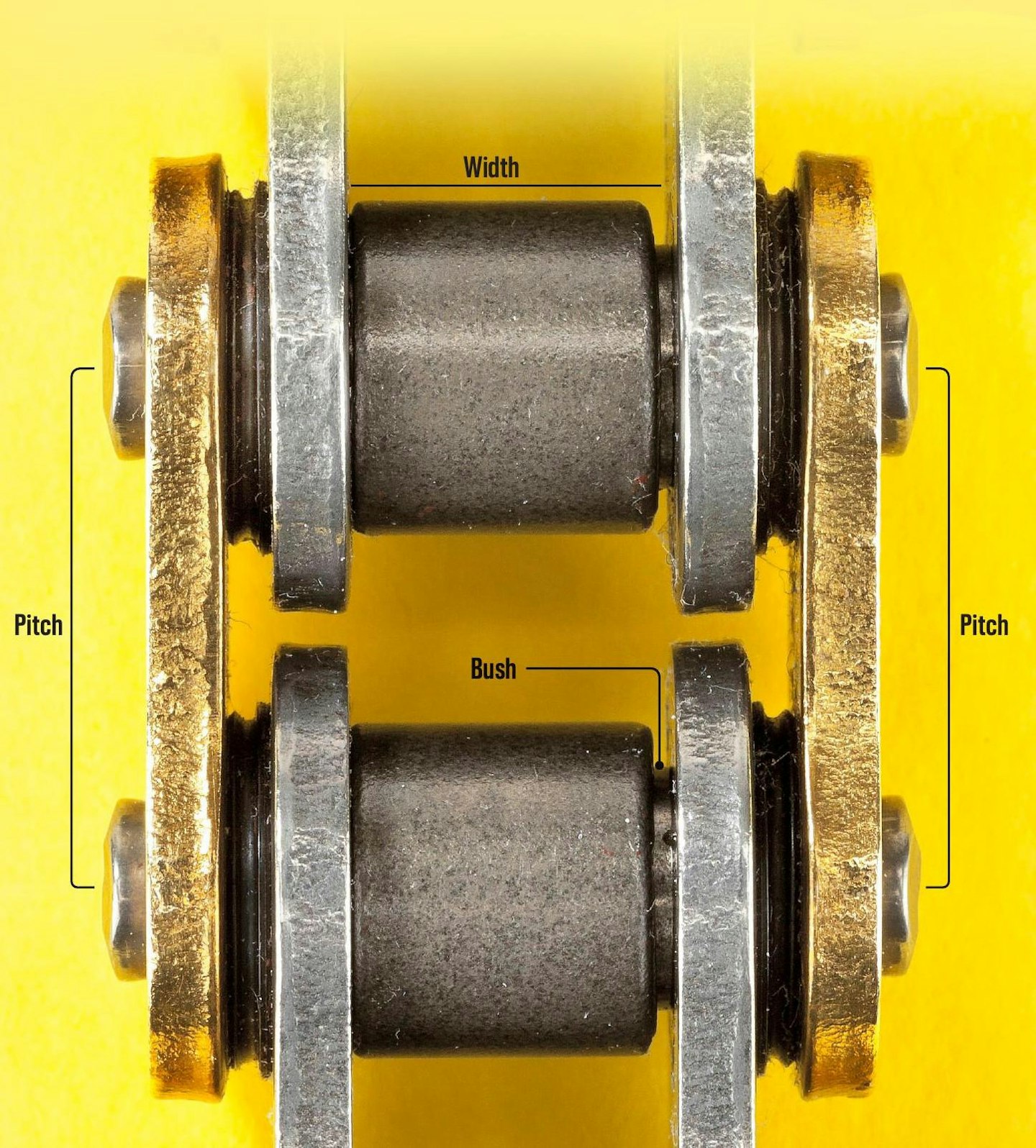

Roller chains are one of the few things that are still produced to imperial measurements, but with a simple three digit code to specify the size: 428, 520, 525 and 530 are the most common.

The first number denotes the pitch of the chain – the distance between the centres of neighbouring pins – and if that distance is ⅝in that number would be ‘5’ (if it were a ‘4’, that would be 4 /8 or ½in; a ‘6’ is 6 /8 or ¾in.)

The next two digits are the measure of the width of the rollers, in that most convenient of measures – eightieths of an inch. So ‘20’ is20 /80in or ¼in. A 520 chain would originally have been specified as5 /8in x ¼in.

If we were referring to a chain with ‘25’ as the second pair of digits, we’d be looking at25 /80in or5 /16in; ‘30’ would mean30 /80in or ⅜in.

It sort of makes sense – imagine how small the print on the sideplates would be if that lot were expressed in millimetres. Although 428 doesn’t quite work with the fractions of 80ths, so we’ll gloss over that.

Which should I fit?

Quality modern chains are remarkable, with 150bhp bikes needing minimal adjustment over thousands of miles. Price apart, fitting a chain with sealing rings looks like a no brainer, but be careful.

Their design makes them wider, which can present issues if retro-fitting to an older classic. Sideplates can vary from 1.5 to 2.6mm, depending on duty type and manufacturer, plus the additional width of the sealing rings. However, modern materials and construction mean that, if sprockets are available, you can often run a narrower chain than the original fitment. The power of most bikes specified with a 530 chain in the 1970s can easily be handled by a modern 520 O-ring.

It is also possible to use O-ring chains on the primary drive of some older classics. This allows the chain case to be run dry, with occasional spray lubrication, eliminating oil bath leaks. However, O-ring chains run hotter than standard chains, so with no oil to aid cooling that may be an issue – as well as clearance and lack of oil to the clutch bearing.

Also, some older bikes require chains with an uneven number of links (some Triumph T140s are 107 links). These require a cranked link, something only easily available for standard chain.

How can I extend chain life?

Simple: keep it clean, correctly adjusted and lubricated. Go for quality over low price and replace chain and sprockets as a set. Gearbox and rear sprockets must be in line – wear on a sprocket’s face can suggest an alignment issue.

Correct adjustment is vital for longevity. Measure free-play in the chain with the suspension loaded unless the manual states otherwise – and check with the wheel at different points of its rotation in case there are tight spots.

Double check free-play once you have re-tightened the wheel spindle, as sometimes a swingarm can open outwards when the spindle is loose, causing the chain to tighten when it’s done up. An over-tight chain will prevent the suspension from working properly, damaging gearbox output and wheel bearings. Too loose can cause vibration or even jumping.

O-ring chains are less fussy about lubrication than conventional items, with most people opting for the convenience of an aerosol chain lube, the majority of which are O-ring safe (but check). Lube has more to do on a standard chain, where it needs to get into the links.