I rode my Rudge round to see Roy the other day. Roy had a ’32 Special in his younger days. A neighbour passed. “Here’s a nice bike for you!” Roy called out. With a cursory glance at the scruffy old Coventry flyer, the neighbour replied: “No, I don’t want one like that, I want the bike that parks round the corner – it’s a Harley-Davidson, that’s a proper English bike.” Roy and I smiled. Hulk Hogan-alikes building choppers on TV seems to have broadened public interest in bikes and while knowledge may still be a bit sketchy, that has to be a good thing. Interest breeds curiosity and the more you know about a subject, generally the more curious you become about it. Learning and passing on information is a big part of humanity and I seldom go to a bike event without learning something I didn’t know.

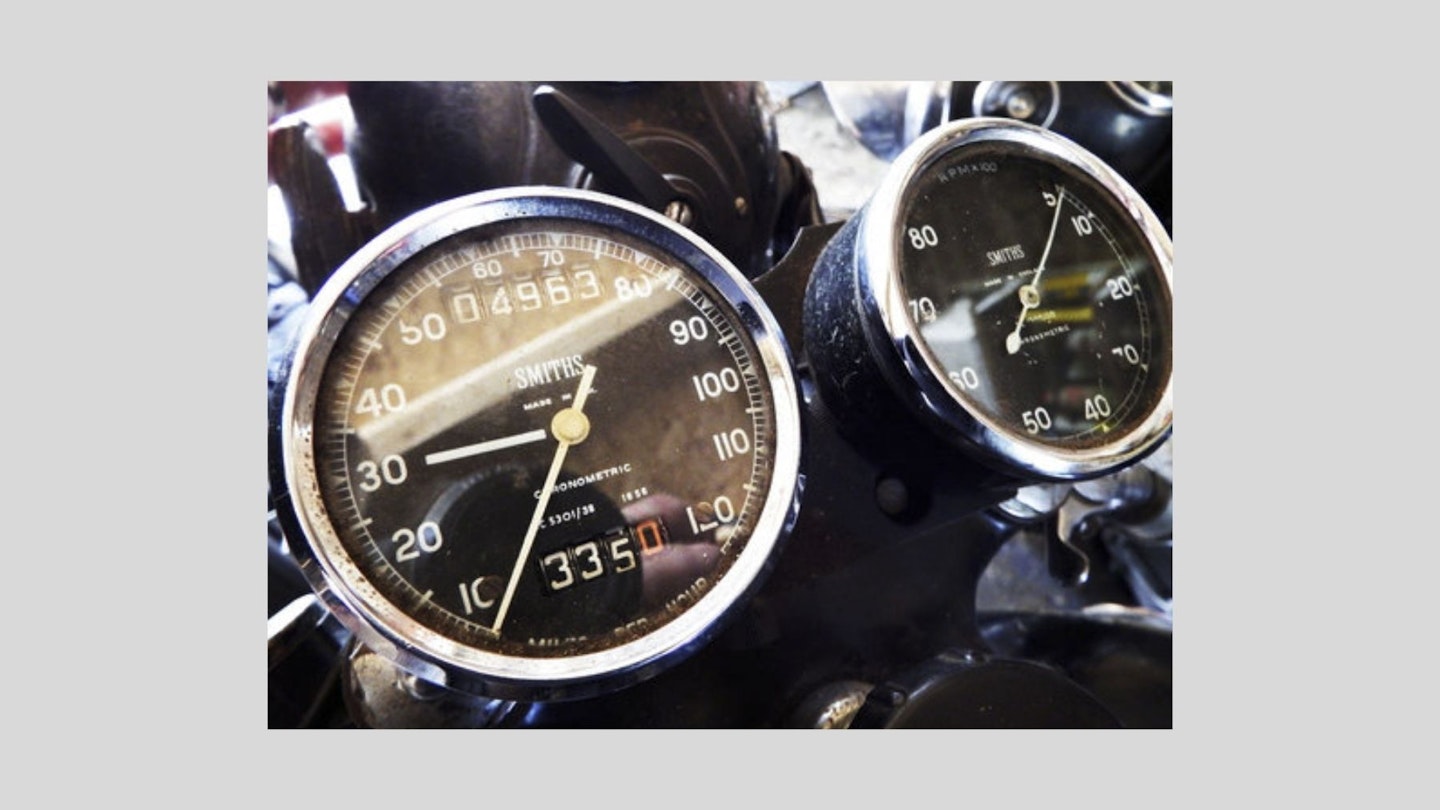

At the last autojumble I visited, I learned two interesting things. The first was from veteran speedometer repairer David Woods. I asked what year the thin white Smith’s chronometric speedo needle with the blob on the bottom went over to a plain thicker type. “It didn’t,” said David. “The thick ones were fitted to rev counters.” The second lesson was even more surprising. “You know why Japanese fours didn’t handle?” asked Maitland Racing’s Tony Huck, casually. “It’s because they cast the holes in the crankcases instead of machining them. The engine bolts were always a rattling fit in the holes, so however much you tightened them, the engine could never properly brace the frame. On the race bikes we used to ream the holes out to accept half-inch studs – it made a huge difference.” Can it be that simple? Tony certainly speaks from experience, so I guess so. I’ve had a few questions concerning core design issues this month – you’ll find them over the page. Meanwhile, I’m off out to sort out my speedo and rev counter needles…

THE BIG FIX

BESET BY OFFSET

RICK GETS ALL RAKISH AS HE DELVES INTO THE SUBJECT OF STEERING GEOMETRY

David Winter is thinking of fitting a T140 Bonneville disc front end to his Triumph Adventurer but says: “I notice my fork legs are further from the fork spindle than the T140 items; will this affect the steering geometry?” This is ‘fork offset’ and T140s have less than older Triumphs. It’s a complex subject, but briefly ‘rake’ is the angle of the steering head to a vertical line. If you followed the rake angle to the ground and measured the distance back to the tyre contact, that is the ‘trail’. Around four inches is common – but the greater the rake, the further that steering head line will be from the tyre contact, so increasing rake (think ‘chopper’) also increases trail. You might think that reducing fork offset – bringing the fork tubes closer to the steering head – reduces trail, but because the tyre contact is already behind the steering head line, moving the forks backwards actually increases trail.

Trail is what provides caster effect. Take a supermarket trolley wheel; you have a vertical steering axis but the wheel is offset to that axis, ‘trailing’ behind, so (unless you get a wonky one) it’s inclined to go straight. Trail offers stability, but slows steering. Increased rake has a similar effect (think ‘chopper’ again), ideal for Highway 61 but less suited to our twisty roads. Altering trail by adjusting yoke offset is much simpler than changing steering head angles and can also be used to restore a reasonable amount of trail to bikes whose rake has more to do with style than steering. The bottom line is, in theory, the lesser offset of the T140 yokes may make the Adventurer a bit heavier to steer but add to its straight-line stability; hopefully David will let us know if it makes a difference.

TOP TIPS

BALANCE PIPES RUMBLE ON AND A METAL MYSTERY

In the balance

Pete McMahon came in on the XS1100 exhaust balance pipe question, saying when he ditched the coupling pipe to fit Norton silencers to his Guzzi Le Mans he found it produced loads more torque, but no top end. With a balance pipe grafted on, the power came back; but sadly the torque was but a memory. Balance pipes can make a big difference to power and torque

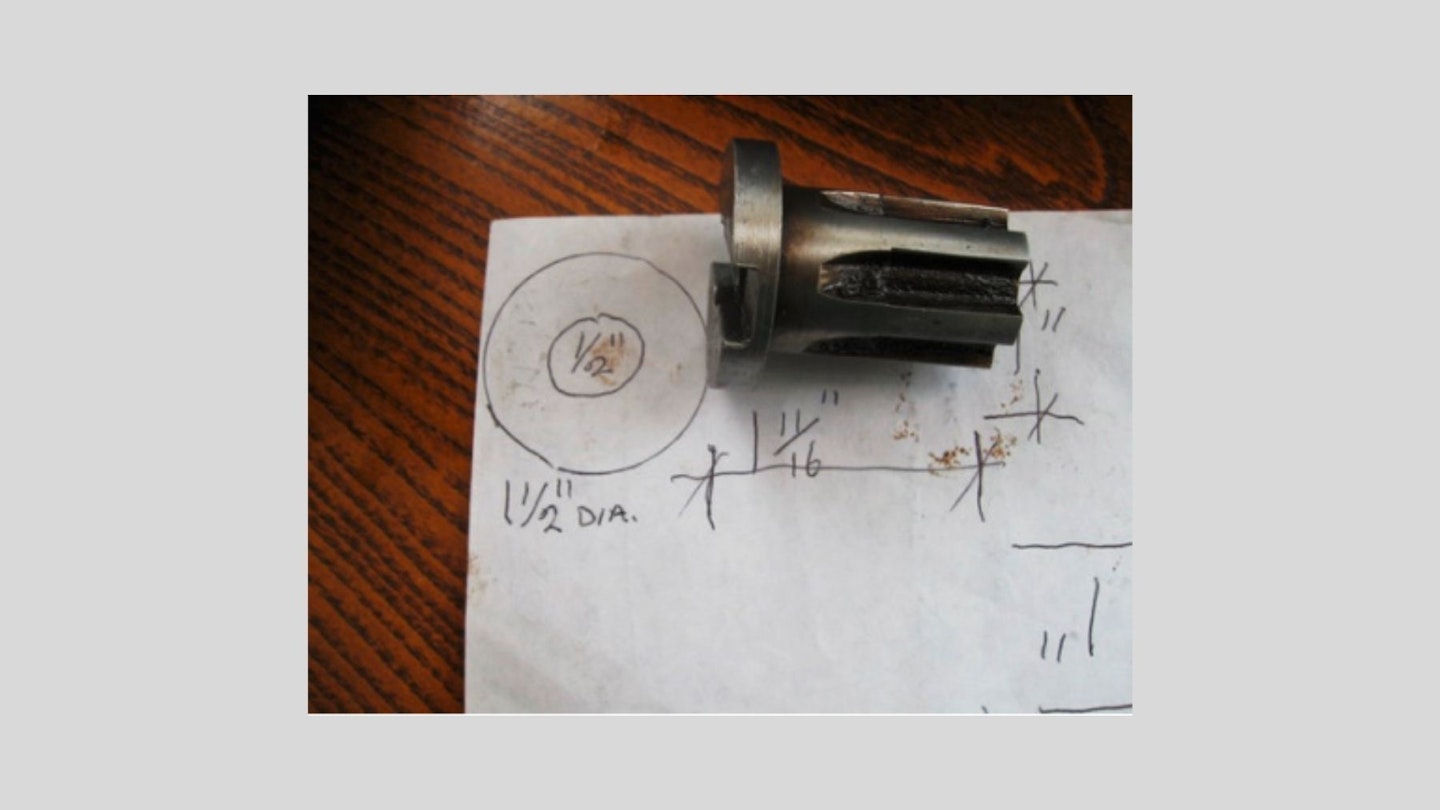

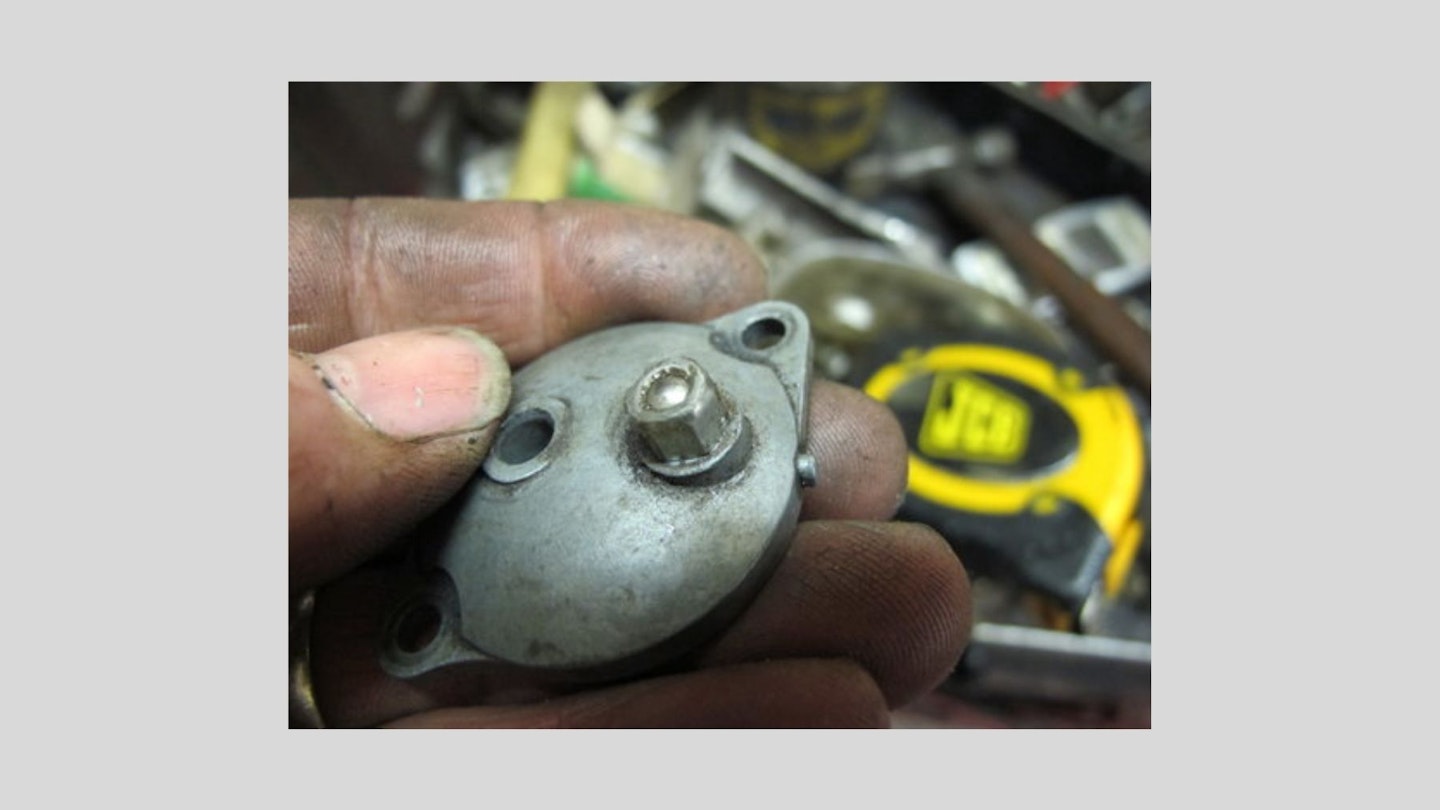

What’s the wotsit?

My mate John Bones sent me this picture of a mystery part. It came in a box of Triumph gearbox bits, but he doesn’t think it looks like a Triumph part and can’t find it in any parts books. I don’t recognise it either and wonder if it’s an engine part at all; it doesn’t look accurately made enough and I wonder if it might be something more like a footrest hanger. That said the slotted fitting on the end reminds me of the end of a 250 Royal Enfield crankshaft. Anyone recognise it? Today’s mystery object. Any suggestions to the usual address

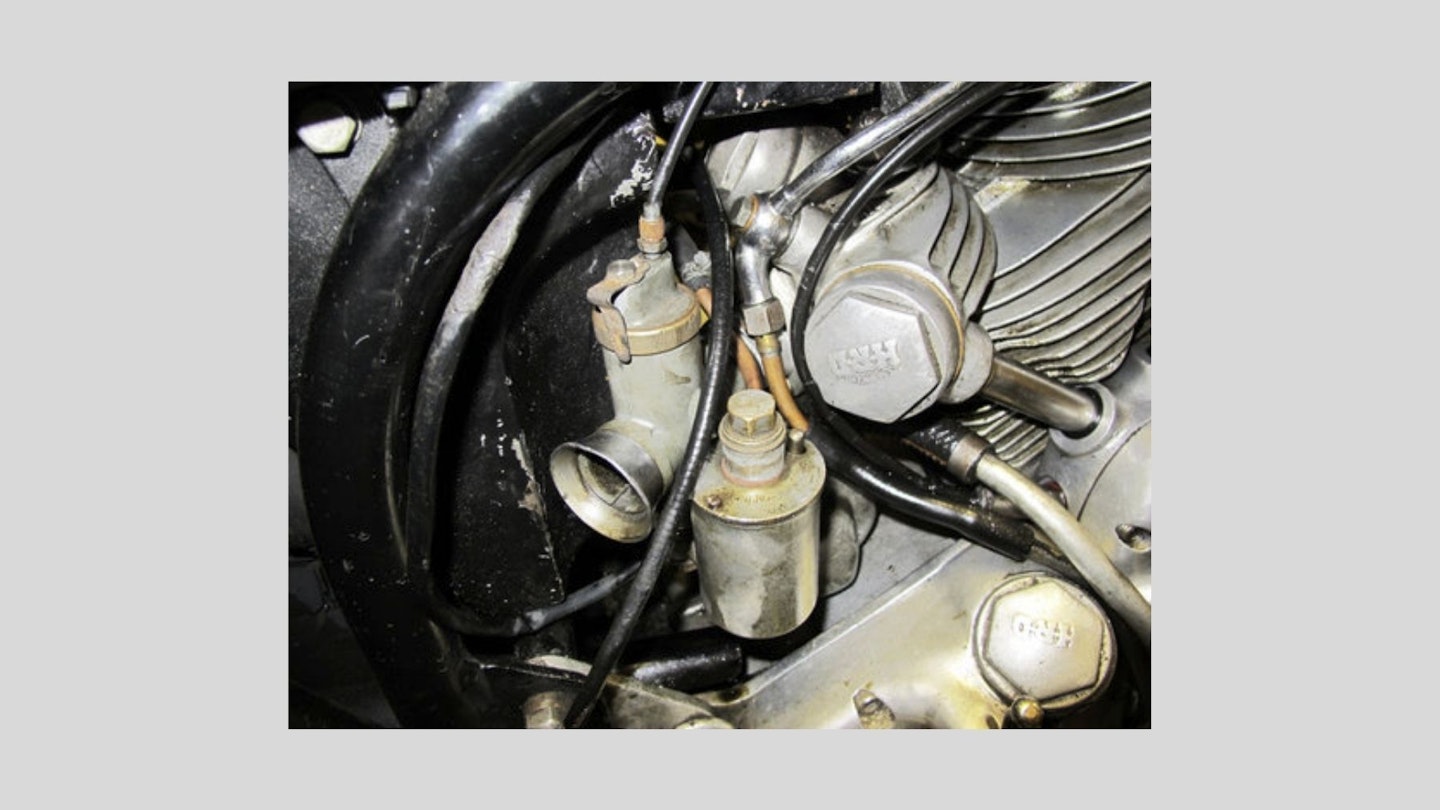

IRREGULAR REGULATORS

While working out what he wants to do with his 350cc Ducati Desmo twin, Gary George thought it was worth looking into the ignition and charging system. The bike came with a spare 500cc engine (evidently bought as a generator donor), a defunct regulator, a supposedly working regulator and a Japanese option. “Is there anyone who can advise on a 21st century ignition/charging system?” Gary asks. I decided to see what Marcus Rex at Rex’s Speedshop (rexsspeedshop. com) thought. “Ah yes,” he said, “These are something I have only recently started looking into. Because these generators have three wires, people presume they’re three-phase and try to fit a stock Japanese regulator. They’re actually single-phase, but with a tapping off the middle of one coil to create a half-wave rectified supply to the ignition circuit. Only the standard regulator will work on this system and there’s room for improvement – but rather than trying to come up with an improved regulator, it made more sense to me to rewind the generator in more conventional style so that a normal rectifier/ regulator can be used. “I have done a couple of Morinis this way so far, but it’s still early days and to be honest I haven’t had enough feedback to make any claims about it yet, but it should work out.” Sounds like a good idea. How often, instead of struggling to find modifications and tricks to make a flawed design work, would it actually be easier – as well as better – to go back to the drawing board and start all over again?

LIMITING FACTORS

Terry Hoare asked a simple question: “Rick, do you know how they work out where to set an engine redline?” I’ve never really thought about that, Terry, but it reminds me of a tale from BSA. Tappet adjustment on late Goldies is done by rotating eccentric rocker spindles and can, in theory, be done on a running engine. Evidently to find the setting for maximum bhp on the dyno, some poor soul had to straddle a screaming engine with spanners in hand... Maybe so, but I can’t see manufacturers revving engines until they explode to work out a rev limit. My feeling was that the limitation is most likely to be the valve gear; springs can’t work faster as engine revs build, so their rate needs to be up to keeping the valve more or less in contact with the cam profile at peak revs. If the cam gets too far ahead of the valve, it won’t be there to lower it onto its seat; snapping shut causes breakage. But making the spring stronger imposes more damaging loads on the valve gear as well as sapping power.

Desmodromic operation, where the valve is lifted and closed by a camdriven rocker, is one answer but it’s complicated and expensive. I had a word with my mate Bruce Hazelgrove, who’s had a bit to do with design and he confirmed my opinion. “Inertia is a huge problem; the faster you go, the more reluctant components are to move – or to stop, so the mass of things like pistons and big-ends will always impose limits. But also just because a valve clears the pistonturning it over on the bench, doesn’t mean it will at 7000rpm. Fortunately there’s plenty of data on limits, allowances for clearance andwhat varying valve weights and springs can do in terms of rpm – which also has to take into account rocker ratios andthe valve train generally. It’s complicated, but it can all be worked out on paper. “Obviously, higher revs means more bangs per minute and more power. Smaller, lighter components allow higher revs (hence multicylinder engines) but in return the engines are heavier, bulkier and more complex. Engine design is always a compromise; you just have to work out what characteristics you want and juggle everything around to achieve it. Once you’ve got ideal valve sizes, cam profile, combustion chamber and piston design worked out, you then look into calculating safe limits for the engine. There’s always experiment, but it isn’t guesswork – people have been studying this for a long time!”

HOW TO

BLANK OFF YOUR AMAL CHOKE HOLE

THE CHOKE ISN’T USUALLY NECESSARY ON AMAL CARBS – HERE’S ONE WAY TO BLOCK THE HOLE IF YOU REMOVE IT

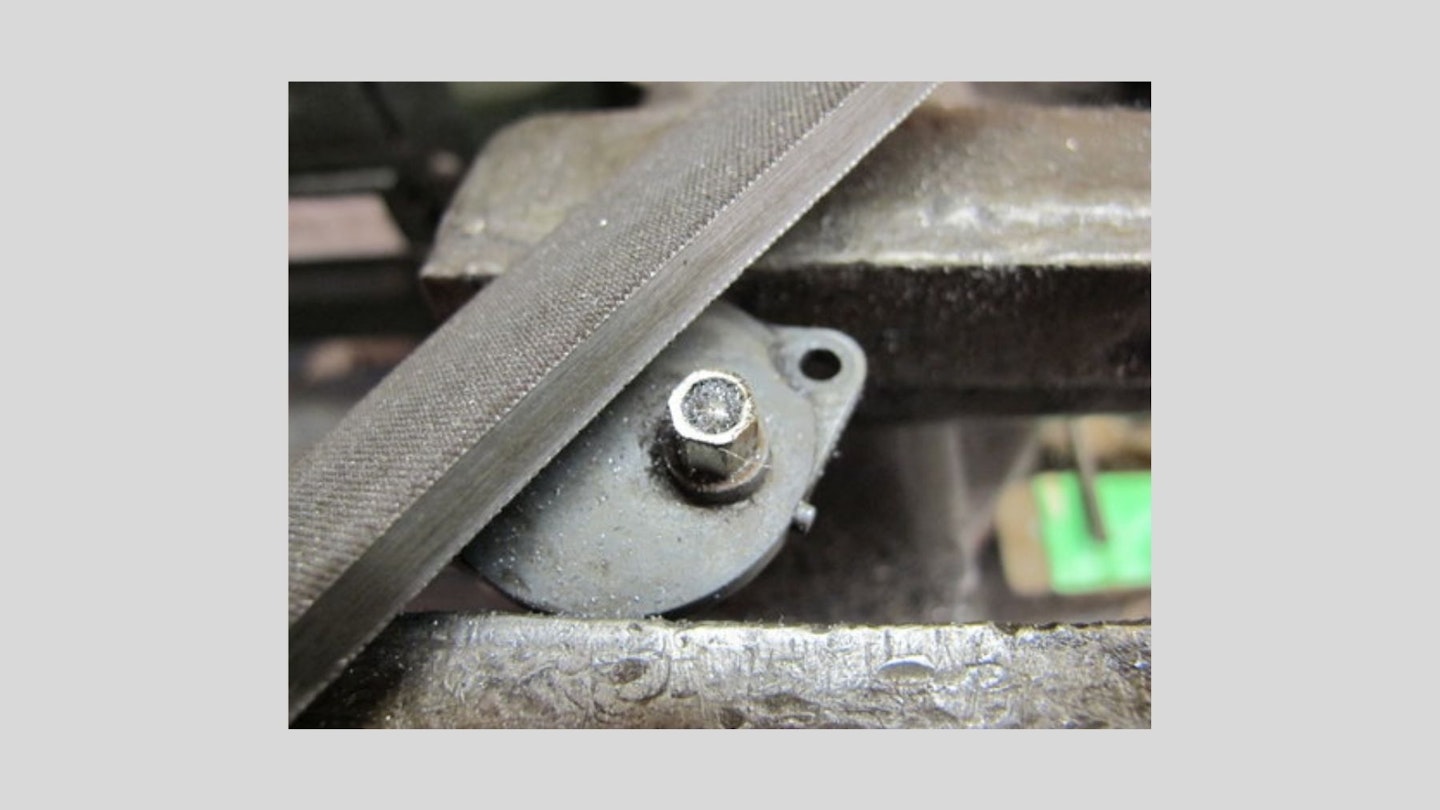

- Amal sell a plug to fit the fine threads in the carb top, but if you don’t have one, a safe way to block the hole in the carb top is to drop a 7/32in ball bearing into the hole.

- You’re going to peen over the end of the adjuster to keep it in place, but the hole is a bit deep. So first, file it down to just over the level of the ball.

- You can just peen over the top with a small hammer, although the adjuster is difficult to hold. A better way is to use a cupped former – this is an old car pushrod.

RUST RETURN

Martin Collyer de-rusted his BSA Gold Star tank last year, using dilute hydrochloric acid, but despite having washed it out carefully he finds the naked steel is rusty again and asks what sealer would best to prevent it happening in future. Personally I prefer to use sealer as a last resort; it’s still unclear how well any of it will cope if and when ethanol levels increase. Sealer dissolving in the fuel causes tiresome carburetter problems and although solvents are around, once in the tank, it’s still difficult to remove. A bit of surface rust in a tank isn’t a big problem – so long as it isn’t flaky, when it starts blocking jets.

Even then, regular use and a fuel filter will gradually clear any loose matter. So in Martin’s case I’d just fit the tank and start using the bike. Leaving it brim full when off the road would avoid further surface rusting, buy ethanol is hygroscopic – it absorbs moisture from the air. Being heavier than petrol, this water pools in the bottom of the tank, and on bikes with bottom seams (Featherbed Nortons and most modern classics) it can creep into seams and start corroding. If I’m taking any bike off the road I drain the tank and leave the cap off so any moisture can evaporate. A little surface rust is better than risking rotting from within.

RICK'S PATCH

THE ANGLE OF DANGLE

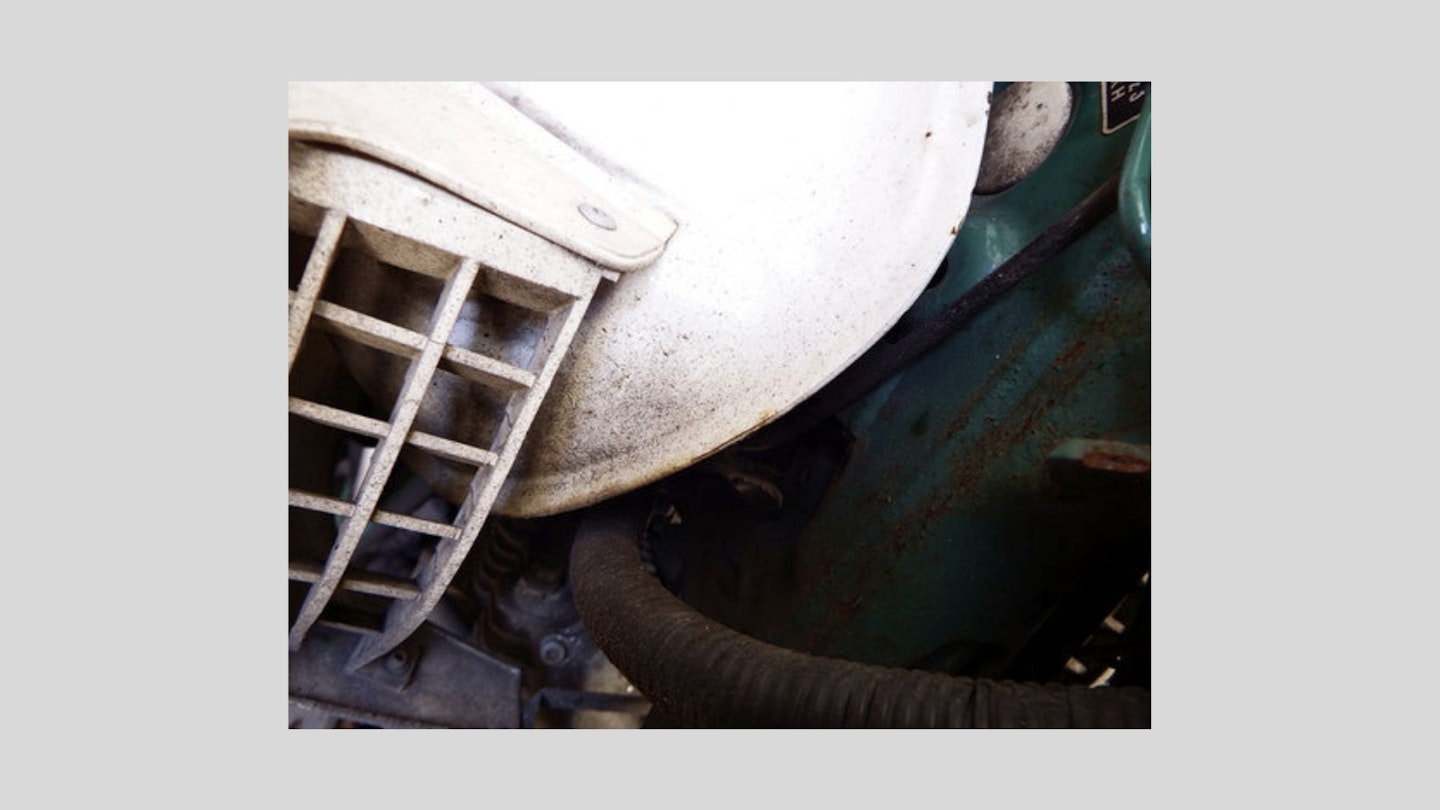

RICK’S NORVIN IS BACK ON THE ROAD BUT IT’S STILL ENJOYING A GOOD LAUGH AT HIS EXPENSE – ESPECIALLY WHEN LEANED OVER

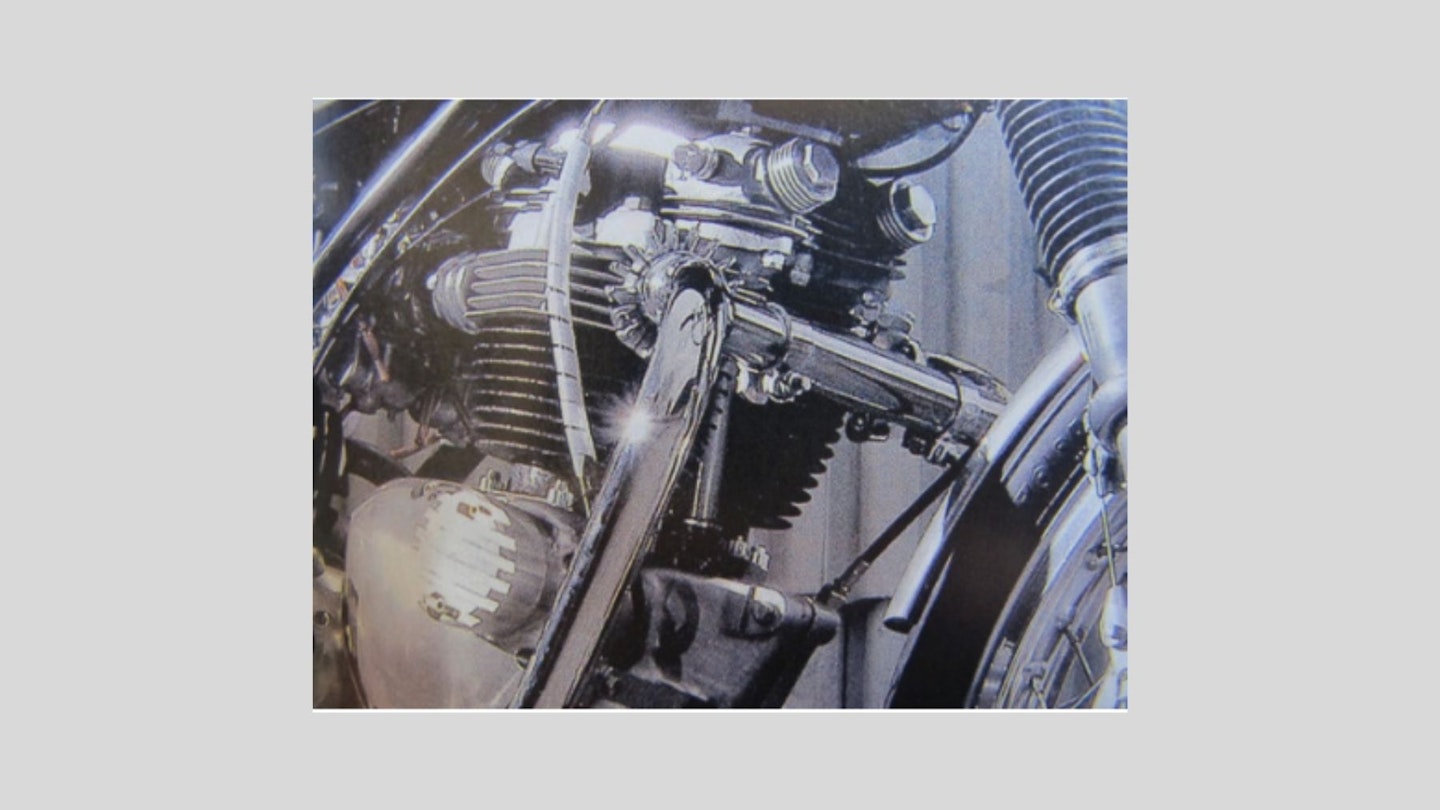

I’m enjoying using the Norvin again, although occasionally it stalls and won’t restart – and because old bikes like nothing better than a hearty laugh at their owners’ expense, it usually happens when the bike’s loaded. Bump-starting a heavy, high-geared, big twin with bulky panniers and tank bag is no joke, I assure you. I knew that riding home from the Ardingly Show with a lucky find BSA trials tank stuffed up my jacket was asking for it. Pulling over to adjust my load, I leaned left and the engine cut; here we go. But, hang on... this recalled something I’ve noticed about the Gold Star; leaning it over to the right makes it splutter, as the level in the side-mounted float bowl artificially rises in relation to the needle jet.

Leaning to the left has the same effect on the Vincent’s rear carb. Is it choking the engine? This time, after a couple of clearing kicks with the valve lifter open, it fired. If float height is already too high, leaning left to kick it over could be the final straw. Mr Triton, Dave Degens, tells me that when he raced Aermacchis for Syd Lawton, Syd used to set the float height to match the angle of the bike as Dave bump-started it to ensure a clean start and getaway. So there’s clearly something in all this – I just need to find out how it applies to me.