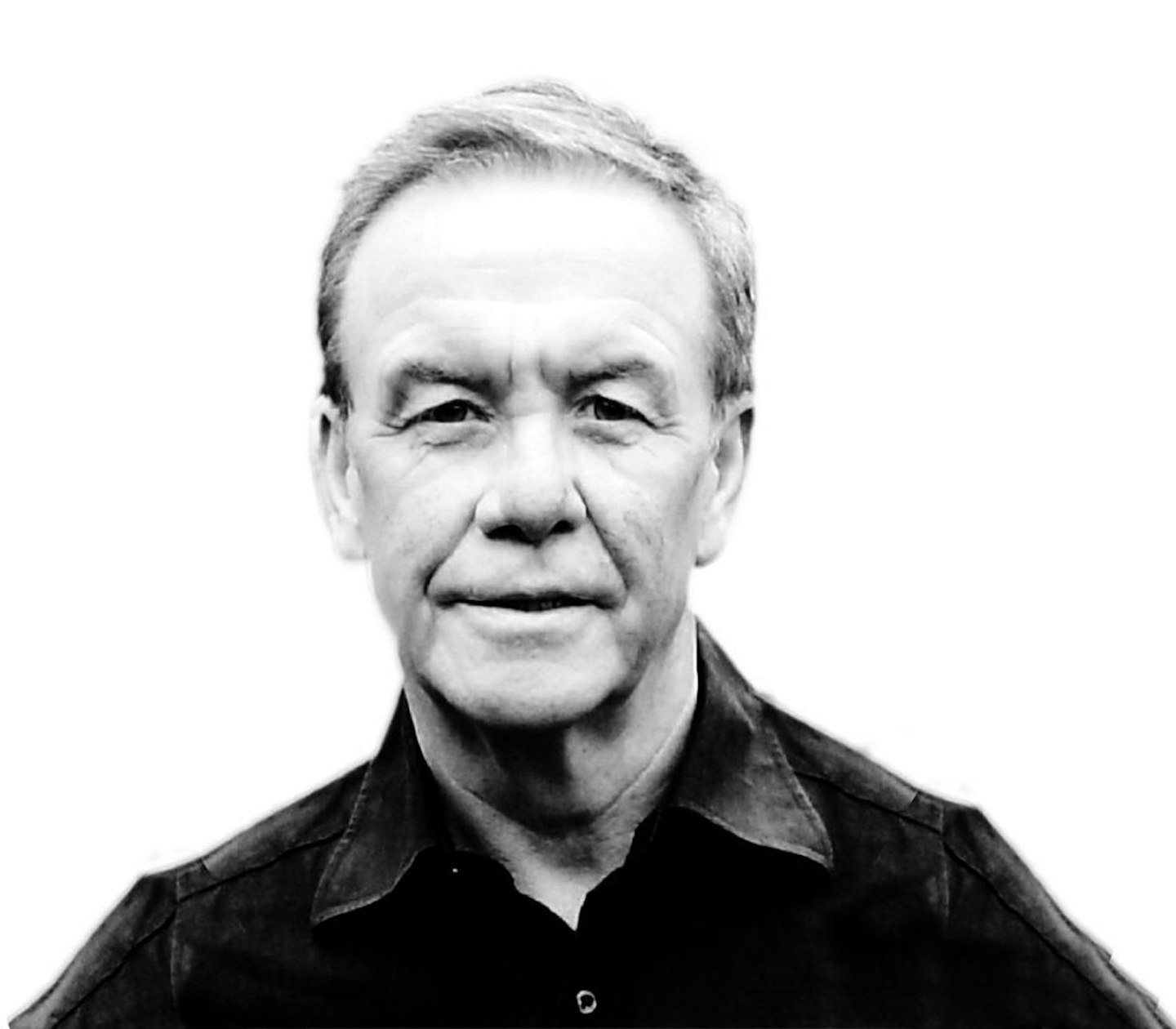

You could keep your Elvis Presleys and your Bobby Moores – Piero Taruffi was my teenage idol. The label ‘Renaissance man’ is these days slapped onto any mediocrity who fits more than one skill into a lifetime. It’s a term applied to the rock pomposity Bono.

Do me a favour. But Taruffi lived up to it; his polymath career included spells as a motorcycle racer, car racer, engineer, team manager, record-breaker, author and international tennis player. Now that’s what I call a Renaissance man.

The reason Taruffi’s name has popped out of my subconsciousness is probably because the four-cylinder Gilera, with which he was associated, is in the news again. Geoff Duke, who died earlier this year, won three world titles on Gileras in the ’50s, and John Surtees’ Norton F-type (featured in this issue, see page 70) was built to rival the four-cylinder machines.

For me, Taruffi had an additional appeal – he was Italian, and had that certain flair and elegance in the way that he presented himself that no Brit can ever achieve. He won his first race at the age of 17, in a Fiat 501 in the Rome-Viterbo event – with his mother and father also in the car. How Italian is that! He later raced AJS, Moto Guzzi and Norton motorcycles.

Taruffi’s link with Gilera started in 1928, at the age of 22, with a machine known as the OPRA. Four-cylinder motorcycles were not unusual, but most – if not all – mounted the engine inline with the frame. A potential disadvantage of this layout is excessive width, but when Taruffi tried the bike he found that the engine protruded no further than the footrests.

He was even more impressed when the OPRA achieved 170kph (106mph), 10kph more than his cammy Norton.

In 1935 he gave the redesigned and renamed machine – now the CNA – its first victory, in the Tripoli Grand Prix. The bike was supercharged, water-cooled and streamlined: “A fantastic project, years ahead of all existing racing designs”, according to Taruffi.

When Giuseppe Gilera bought CNA’s six existing machines when the company changed ownership in 1936, he invited Taruffi, who by then had graduated in mechanical engineering, to be the team’s technical and team manager. The pressedsteel frame was abandoned for a tubular one, and the loose-roller main bearings, which had a life of only 300km (186 miles), were replaced with a stronger arrangement good for 3000km.

In 1937 Taruffi captured the world motorcycle land speed record, when he guided the 492cc Gilera to an average of 170.27mph. Among its pre-war successes, the Gilera won the 1939 European 500cc Championship and the 1939 European hillclimb title. By that time the machine was giving 80bhp at 9000rpm, although its weight had grown to 396lb (180kg).

When Taruffi switched to cars, he drove works cars for Ferrari, Maserati, Alfa Romeo and Mercedes-Benz. He won just one of his 18 F1 events – the 1952 Swiss GP in a two-litre Ferrari 500 – but in a total of 136 car races he was victorious 44 times.

Taruffi’s last race in 1957 marked a fitting climax to his career, but also one marked with tragedy. It occurred in the Mille Miglia, that 1000-mile blast around Italy on public roads that to my mind will always be the most fantastic event in the history of car and motorcycle sport. Taruffi was handed a factory 4.1-litre Ferrari, a V12 monster probably capable

of around 180mph. Taruffi won, but another Ferrari factory driver, Alfonso de Portago, plunged off the road and 14 people were killed. This followed the 1955 Le Mans disaster and its 80 victims. Taruffi, then 50, pledged to his wife Isabella that he would never race again.

Later that year he wrote an article, ‘Stop us before we kill again’, that appeared in the Saturday Evening Post in the USA. In 1959 he published his book The Technique of Motor Racing. An accepted classic (motorcycle racers could also benefit from it), remarkably you can still buy it for £30. I remember reading it as a teenager. It’s time to re-invest in it...